Rice simulations demonstrate 1-D material’s stiffness, electrical versatility

Hold on, there, graphene. You might think you’re the most interesting new nanomaterial of the century, but boron might already have you beat, according to scientists at Rice University.

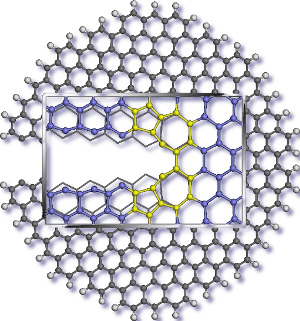

A Rice team that simulated one-dimensional forms of boron — both two-atom-wide ribbons and single-atom chains — found they possess unique properties. The new findings appear this week in the Journal of the American Chemical Society.

For example, if metallic ribbons of boron are stretched, they morph into antiferromagnetic semiconducting chains, and when released they fold back into ribbons.

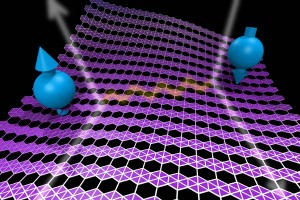

Rice scientists calculate tweaks to graphene would form phonon-friendly cones

Rice scientists calculate tweaks to graphene would form phonon-friendly cones

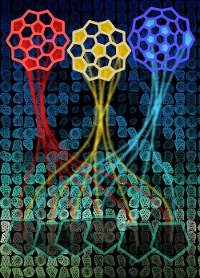

When is nothing really something? When it leads to a revelation about

When is nothing really something? When it leads to a revelation about  Graphane

Graphane